Chapter 5

Chapter 5

Civil Service Discipline

5.1

It is the duty of all civil servants to work with dedication and diligence, and spare no effort in delivering quality service to the community. To maintain the integrity and efficiency of the public service, and sustain the community’s trust in the Government, civil servants have to uphold the highest standard of conduct and discipline at all times. To this end, the Government has put in place a well-established disciplinary system ensuring that any civil servant who violates Government rules and regulations is disciplined and those breaking the law are brought to justice.

5.2

The Commission collaborates with the Government to maintain the highest standard of conduct in the Civil Service. With the exception of exclusions specified in the PSCO14, the Administration is required under s.18 of the PS(A)O15 to consult the Commission before imposing any punishment under s.9, s.10 or s.11 of the PS(A)O upon a Category A officer. This covers virtually all officers except those on probation or agreement and some who are remunerated on the Model Scale 1 Pay Scale. At the end of June 2024, the number of Category A officers falling within the Commission’s purview for disciplinary matters was about 123 800.

14

Please refer to paragraph 1.4 of Chapter 1.

15

Please refer to paragraph 1.5 of Chapter 1.

5.3

The Commission’s advice on disciplinary submissions is based on facts and objective evidence, supported by full investigations conducted by the relevant B/Ds. While the nature and gravity of the misconduct or offence are our primary consideration, we are also mindful of the need to maintain broad service-wide consistency in disciplinary standards, protect the right of the representations by the accused and at the same time respond to changing times and public expectations.

5.4

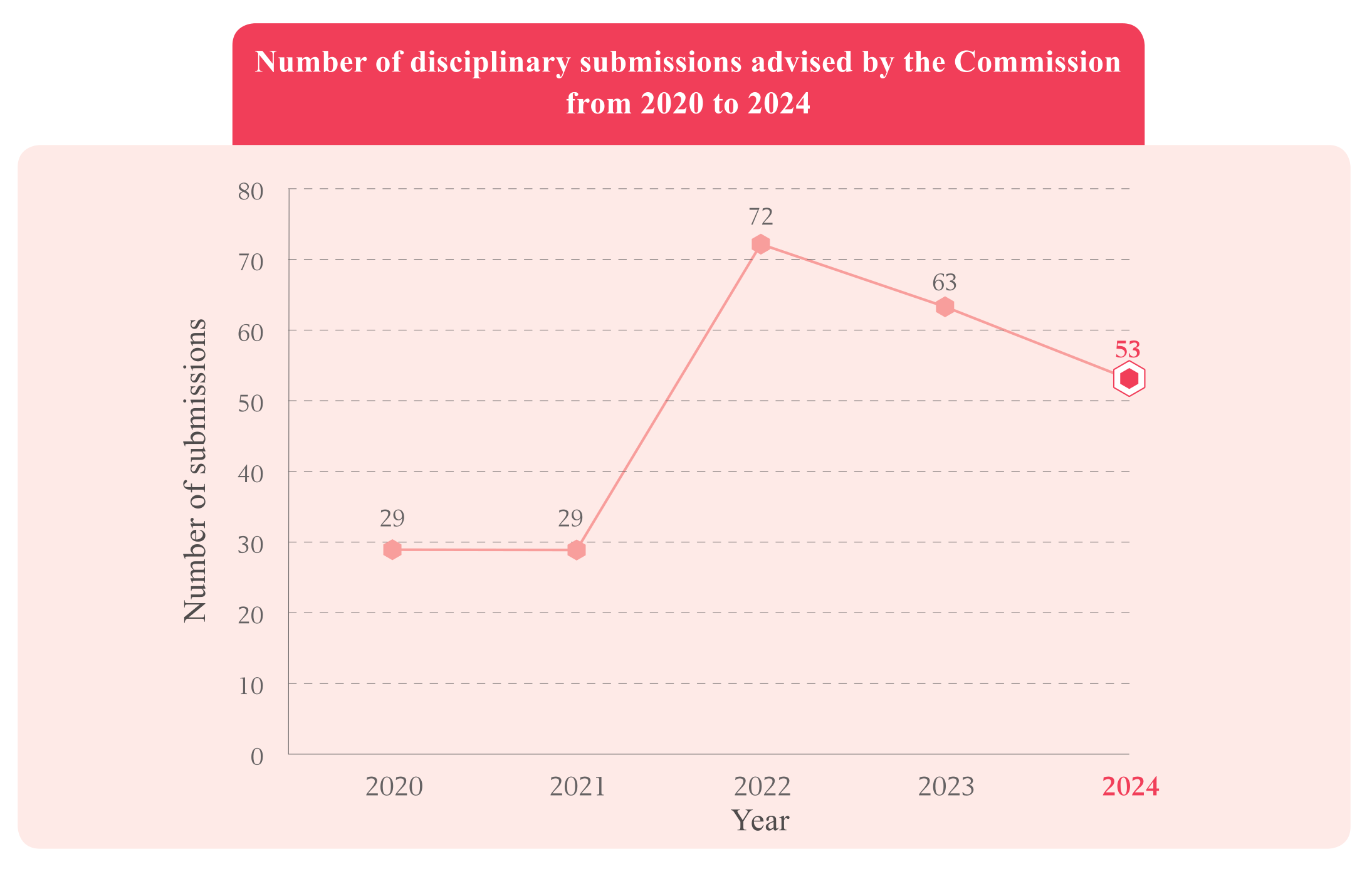

In 2024, the Commission advised on 53 disciplinary submissions which had gone through the formal disciplinary procedures prescribed under the PS(A)O. It represents about 0.04% of the 123 800 Category A officers within the Commission’s purview. The number of disciplinary submissions as advised by the Commission in the past five years is shown below –

5.5

As shown in the above chart, the number of disciplinary submissions advised by the Commission has remained consistently low in the past five years. It indicates that the great majority of our civil servants have continued to measure up to the very high standard of conduct and discipline required of them. Nonetheless, there is no room for complacency in the concerted efforts to uphold a civil service of high integrity and probity. CSB has assured the Commission that it will sustain its efforts in promoting good standards of conduct and integrity through training, seminars as well as the promulgation and updating of rules and guidelines. The Commission will, as always, remain vigilant and collaborate with the Government to ensure equity, fairness and maintenance of broad consistency in punishment throughout the service.

5.6

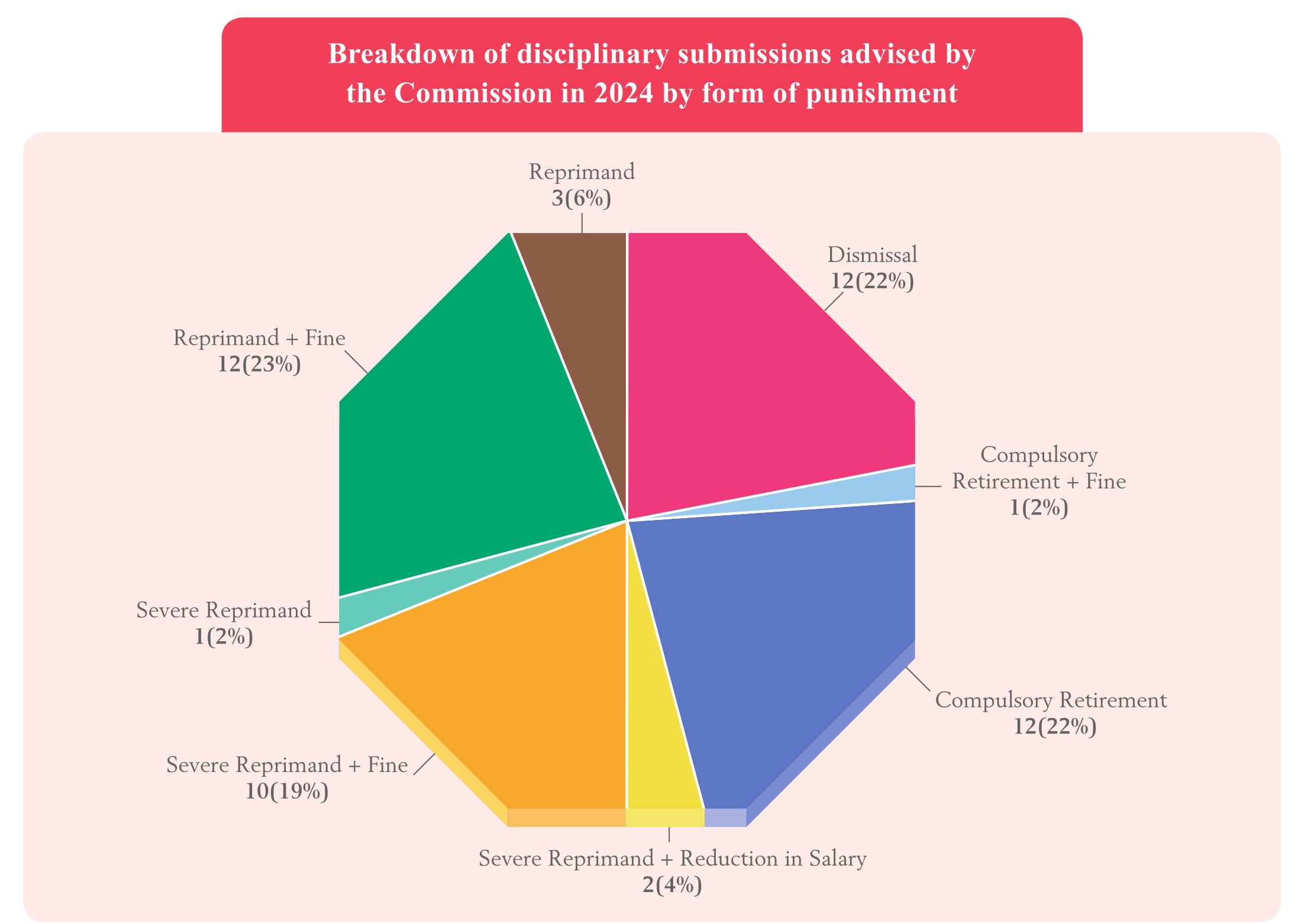

To illustrate the nature of the 53 disciplinary submissions advised by the Commission in 2024, a breakdown by category of criminal offence/misconduct and salary group is at Appendix IX. As depicted in the pie chart below, nearly half of the submissions had resulted in the removal of the civil servants concerned from the service by “compulsory retirement”16 or “dismissal”17, while a quarter had resulted in the officers receiving the punishment of “severe reprimand”18. In about 48% of the submissions, a financial penalty was added in the form of a “fine”19 or a “reduction in salary”20. These figures bear testimony to the resolute stance that the Government has taken against civil servants who have committed acts of misconduct or criminal offences.

16

An officer who is compulsorily retired may be granted retirement benefits in full or in part, and in the case of a pensionable officer, a deferred pension when he reaches his statutory retirement age.

17

Dismissal is the most severe form of punishment as the officer forfeits his claims to retirement benefits (except the accrued benefits attributed to the Government’s and the officer’s mandatory contribution under the Mandatory Provident Fund Scheme or the Civil Service Provident Fund Scheme).

18

A severe reprimand will normally debar an officer from promotion or appointment for three to five years. This punishment is usually recommended for more serious misconduct/criminal offence or for repeated minor misconduct/criminal offences.

19

A fine is the most common form of financial penalty in use. On the basis of the salary-based approach, which has become operative since 1 September 2009, the level of fine is capped at an amount equivalent to one month’s substantive salary of the defaulting officer.

20

Reduction in salary is a form of financial penalty by reducing an officer’s salary by one or two pay points. When an officer is punished by reduction in salary, salary-linked allowance or benefits originally enjoyed by the officer would be adjusted or suspended in the case where after the reduction in salary the officer is no longer on the required pay point for entitlement to such allowance or benefits. The defaulting officer can “earn back” the lost pay point(s) through satisfactory performance and conduct, which is to be assessed through the usual performance appraisal mechanism. In comparison with a “fine”, reduction in salary offers a more substantive and punitive effect. It also contains a greater “corrective” capability in that it puts pressure on the officer to consistently perform and conduct himself up to the standard required of him in order to “earn back” his lost pay point(s).

Reviews and Observations on Disciplinary Issues

5.7

The Commission has been working in close partnership with the Government to identify, develop and promote good practices in the management of the Civil Service. As reported in Chapter 2 of this Annual Report, CSB has undertaken to review the PS(A)O and PS(D)R with a view to enhancing the civil service disciplinary mechanism. The Commission will provide advice when CSB consults us on its preliminary proposals in 2025.

5.8

Separately, we are glad to see that the Secretariat on Civil Service Discipline (SCSD) has maintained its out-reach visits to B/Ds to explore scope to enhance mutual efficiency in processing disciplinary cases. Recognising that personnel assigned and the investigation techniques they possess are pivotal to the successful conclusion of disciplinary cases, SCSD has acted on the Commission’s advice and continued to arrange capacity building workshops for investigation work on disciplinary cases. Such workshops are open to appointment practitioners as well as departmental managers who are responsible for day-to-day staff management. The Commission will continue to collaborate with CSB, and provide feedback and suggestions to facilitate its pursuit of the training initiatives.

5.9

Apart from deliberating and advising on the appropriate level of punishment for the cases it received for advice, the Commission also makes observations on them and initiates discussions with CSB to explore scope for improvement in handling disciplinary cases or staff management. In the ensuing paragraphs, we will highlight some of the observations and recommendations we have tendered in the year.

Processing time of disciplinary cases

5.10

The Commission accepts that more time is required to consider cases with complications. However, failure to take timely action in processing disciplinary cases not only weakens the credibility of the disciplinary system, the Government’s determination in upholding a high standard of probity in the Civil Service would also be undermined. In the past year, the Commission noted with concern that it took the Departments concerned exceedingly long time to conclude the disciplinary cases as illustrated in Cases 5A and 5B.

Case 5A

An officer was suspected to have manipulated his official account of a departmental computerised system for private convenience and gains. After investigation, the Department found that the officer had abused the use of his official account on 70 occasions over a period of seven years albeit the total amount of government loss involved was not significant.

In view of the seriousness of the case, the Department reported it to a law enforcement agency (LEA) for follow up. Discounting the time spent by the LEA to investigate into the case and conclude that no criminal proceedings would be taken against the officer, the Department spent another three years to conduct its investigation, gather the necessary information and seek legal advice before initiating formal disciplinary proceedings against him. The Department attributed the long processing time to reasons such as substantial volume of information involved, heavy workload and stringent manpower situation. Although the officer was ultimately removed from the service given the gravity of his misconduct, the Commission considered the prolonged processing time unacceptable. We had drawn the case to the personal attention of the HoD concerned.

At the request of the Commission, the HoD has submitted a review report on the handling process of the Department, admitting the need for making improvements. The report sets out a series of measures to be implemented to avoid recurrence of similar delays in processing disciplinary cases. Besides, the Department is committed to launching a new computerised system in 2025 with built-in features to prevent abusive use by staff.

While appreciating the HoD’s undertaking to make improvements, the Commission has reminded the Department to review the effectiveness of the measures on a regular basis so that refinement/enhancement could be made promptly and diligently to achieve the required effects.

In view of the seriousness of the case, the Department reported it to a law enforcement agency (LEA) for follow up. Discounting the time spent by the LEA to investigate into the case and conclude that no criminal proceedings would be taken against the officer, the Department spent another three years to conduct its investigation, gather the necessary information and seek legal advice before initiating formal disciplinary proceedings against him. The Department attributed the long processing time to reasons such as substantial volume of information involved, heavy workload and stringent manpower situation. Although the officer was ultimately removed from the service given the gravity of his misconduct, the Commission considered the prolonged processing time unacceptable. We had drawn the case to the personal attention of the HoD concerned.

At the request of the Commission, the HoD has submitted a review report on the handling process of the Department, admitting the need for making improvements. The report sets out a series of measures to be implemented to avoid recurrence of similar delays in processing disciplinary cases. Besides, the Department is committed to launching a new computerised system in 2025 with built-in features to prevent abusive use by staff.

While appreciating the HoD’s undertaking to make improvements, the Commission has reminded the Department to review the effectiveness of the measures on a regular basis so that refinement/enhancement could be made promptly and diligently to achieve the required effects.

Case 5B

A complaint was received by a Department which alleged that an officer had committed multiple misconduct acts, the establishment of which might likely lead to a removal punishment for the officer.

The Department spent more than two years to conduct investigation and initiate disciplinary proceedings. It took another 2.5 years for conducting disciplinary hearings mainly due to the officer’s sickness, rendering him unfit to attend the hearings at various stages during the inquiry process. The inquiry report was subsequently prepared ten months after finishing the inquiry hearings.

Suspecting that his misconduct acts would have been established, the officer resigned after the inquiry by giving one month’s salary in lieu of notice before any punishment could be imposed on him.

Apparently, the officer’s resignation was to avoid disciplinary punishment as it would have led to his dismissal without retirement benefits given the seriousness of his established misconduct acts.

While the Department had withheld the release of the officer’s retirement benefits upon his resignation, it needed to seek the Commission’s advice timely on forfeiting his retirement benefits wholly in accordance with the established guidelines. However, the case was only submitted to the Commission three years after the officer’s resignation. Upon receipt of the Commission’s support of the recommendation to forfeit the officer’s retirement benefits, the case had dragged on for almost nine years.

While appreciating the complexity of the case and the requirement of observing due process, the acute delay was totally unacceptable. The Commission has requested the HoD concerned to make a report to us setting out clearly the reasons for such a long processing time and the measures taken/to be taken for avoidance of future recurrence. The Commission looks forward to the positive feedback from the HoD.

The Department spent more than two years to conduct investigation and initiate disciplinary proceedings. It took another 2.5 years for conducting disciplinary hearings mainly due to the officer’s sickness, rendering him unfit to attend the hearings at various stages during the inquiry process. The inquiry report was subsequently prepared ten months after finishing the inquiry hearings.

Suspecting that his misconduct acts would have been established, the officer resigned after the inquiry by giving one month’s salary in lieu of notice before any punishment could be imposed on him.

Apparently, the officer’s resignation was to avoid disciplinary punishment as it would have led to his dismissal without retirement benefits given the seriousness of his established misconduct acts.

While the Department had withheld the release of the officer’s retirement benefits upon his resignation, it needed to seek the Commission’s advice timely on forfeiting his retirement benefits wholly in accordance with the established guidelines. However, the case was only submitted to the Commission three years after the officer’s resignation. Upon receipt of the Commission’s support of the recommendation to forfeit the officer’s retirement benefits, the case had dragged on for almost nine years.

While appreciating the complexity of the case and the requirement of observing due process, the acute delay was totally unacceptable. The Commission has requested the HoD concerned to make a report to us setting out clearly the reasons for such a long processing time and the measures taken/to be taken for avoidance of future recurrence. The Commission looks forward to the positive feedback from the HoD.

5.11

CSB is also concerned about the need to process disciplinary cases in a timely manner. Starting from January 2024, B/Ds have been required to report on a half-yearly basis to their senior management and CSB on the progress of their handling of disciplinary cases with a view to stepping up the monitoring of the processing time of disciplinary cases, and ensuring that punishments meted out are commensurate with the gravity of the misconduct concerned. The Commission is glad to note the positive actions taken by CSB. We expect to see more speedy and proper processing of disciplinary cases in the coming year.

Handling of disciplinary cases

5.12

Timeliness aside, a robust and decisive approach in handling disciplinary cases will send a clear message to staff that inappropriate behaviours are not tolerated, reinforcing the standards expected within the Civil Service so as to maintain a professional and accountable workforce. Cases 5C and 5D illustrate the importance for B/Ds to be decisive in action to initiate formal disciplinary actions against officers committing misconduct acts.

Case 5C

An officer was convicted of having assaulted his co-worker while they were working in a public venue. As the officer was a repeat offender with records of various workplace assaults against his co-workers, and on one occasion, against a member of the public, the Commission supported the Department’s recommendation that a removal punishment should be imposed on the defaulting officer.

Upon scrutiny of the case, the Commission noted that the officer, with a medical history of mental illness, had been reported to have problems in emotion management and interpersonal skills since his early stage of appointment. As shown in his appraisal reports, the behavioural issues and communication problems had persisted for several years, and seriously affected the daily operation and staff morale of the office. Instead of taking robust management actions in good time to address the problems, the supervisors maintained a compassionate approach by giving him routine advice and calling special appraisal reports on him to monitor his performance over the years.

While the case needed to be handled with care in view of the officer’s medical history, more vigilant and decisive management actions should have been taken earlier in view of his aggravated and persistent behavioural and performance issues. Prompt action was especially called for to deter his misconduct acts so as to avoid posing further nuisance or even safety risk to his colleagues and members of the public.

The Commission has expressed concern to the Department about its indecisiveness and leniency in handling the case. Taking reference from this case, the Department should remind all supervising officers and the grade management to be more robust and stringent in managing staff with conduct issues.

Upon scrutiny of the case, the Commission noted that the officer, with a medical history of mental illness, had been reported to have problems in emotion management and interpersonal skills since his early stage of appointment. As shown in his appraisal reports, the behavioural issues and communication problems had persisted for several years, and seriously affected the daily operation and staff morale of the office. Instead of taking robust management actions in good time to address the problems, the supervisors maintained a compassionate approach by giving him routine advice and calling special appraisal reports on him to monitor his performance over the years.

While the case needed to be handled with care in view of the officer’s medical history, more vigilant and decisive management actions should have been taken earlier in view of his aggravated and persistent behavioural and performance issues. Prompt action was especially called for to deter his misconduct acts so as to avoid posing further nuisance or even safety risk to his colleagues and members of the public.

The Commission has expressed concern to the Department about its indecisiveness and leniency in handling the case. Taking reference from this case, the Department should remind all supervising officers and the grade management to be more robust and stringent in managing staff with conduct issues.

Case 5D

An officer, who had been serving in his Department for six years, was recommended for dismissal in 2024 as he had been late for work persistently despite repeated reminders and warnings from his supervisors. The Commission was concerned that the Department only instituted formal disciplinary action against the officer when he had been late for work for an aggregate of more than 950 hours (or equivalent to some 100 working days) over a long span of three years.

On a closer examination of the case, the Commission noted that the officer’s lateness problem was first reported in his appraisal during the second year of his probationary service. Yet, the Department confirmed him to the permanent establishment after his serving three years of probation merely on the basis of his slight improvements in attendance and general satisfactory performance.

Ironically, the Department began deducting the officer’s salary under the “no work, no pay” principle as stipulated in CSR 610 shortly before his confirmation to the permanent establishment (i.e. when he was still serving on probationary terms). It was apparent that the Department had failed to holistically assess his overall suitability for long-term appointment. This lenient approach conveyed a misleading message to the officer, suggesting that his misconduct was of little consequence and could simply offset by salary deductions. The officer was eventually dismissed, by when his lateness problem had further deteriorated and persisted for more than three years.

The Commission has drawn the case to the personal attention of the HoD and reiterated the need for making improvements in staff management. The Department should also remind all supervising officers of the importance of taking a more resolute approach in handling misconduct cases so that defaulting officers could be punished in a timely manner and could clearly understand the consequence of their misconduct acts.

On a closer examination of the case, the Commission noted that the officer’s lateness problem was first reported in his appraisal during the second year of his probationary service. Yet, the Department confirmed him to the permanent establishment after his serving three years of probation merely on the basis of his slight improvements in attendance and general satisfactory performance.

Ironically, the Department began deducting the officer’s salary under the “no work, no pay” principle as stipulated in CSR 610 shortly before his confirmation to the permanent establishment (i.e. when he was still serving on probationary terms). It was apparent that the Department had failed to holistically assess his overall suitability for long-term appointment. This lenient approach conveyed a misleading message to the officer, suggesting that his misconduct was of little consequence and could simply offset by salary deductions. The officer was eventually dismissed, by when his lateness problem had further deteriorated and persisted for more than three years.

The Commission has drawn the case to the personal attention of the HoD and reiterated the need for making improvements in staff management. The Department should also remind all supervising officers of the importance of taking a more resolute approach in handling misconduct cases so that defaulting officers could be punished in a timely manner and could clearly understand the consequence of their misconduct acts.

A robust and decisive approach in handling disciplinary cases will send a clear message that inappropriate behaviours are not tolerated.

Supervisory accountability

5.13

It is beyond doubt that defaulting officers are held directly accountable for their misconduct acts. At the same time, B/Ds should be on constant alert to ensure the robustness of the control/monitoring mechanism of their departmental operation. Effective daily staff management is key to the maintenance of a high standard of staff conduct and discipline, and is clearly more constructive than taking punishment action after the occurrence of misconduct. Omission and non-performance of duties, especially committed over a period of time, should have been detected and avoided if supervisors could discharge their supervisory and monitoring responsibilities properly and diligently, as illustrated in Cases 5E and 5F.

Case 5E

This case concerns an officer who was criminally convicted of “Theft”. In examining the misconduct case, the Department found that the defaulter was arrested in a supermarket while he was away from office without approval. The defaulter and his two co-workers worked under the same supervisor in a public venue. Working on a two-shift pattern, they were assigned to take either shift depending on the operational needs.

On the material day, the defaulter and one officer worked on one shift, whereas the supervisor and the other officer on the other. Before the scheduled off-duty time on the day, the defaulter told his co-worker on the same shift that he would go out for making some purchases. Both of them did not notify the supervisor, reflecting the lax office discipline and deficiency in staff management. The supervisor only came to know the defaulter’s unauthorised absence when the latter reported to the Department about his arrest by a LEA.

Upon the Commission’s request, the Department has subsequently enhanced its monitoring of staff attendance at the venue with staff supervision tightened up. Noting that there are other offices with staff working on shifts, we have also advised the Department to –

(a) consider extending the monitoring measures to all these offices;

(b) clearly advise all staff of the standard of conduct required to ensure that proper office discipline is maintained at all times; and

(c) remind all supervisors that they are held accountable in maintaining both office operation and proper office discipline under their purview.

On the material day, the defaulter and one officer worked on one shift, whereas the supervisor and the other officer on the other. Before the scheduled off-duty time on the day, the defaulter told his co-worker on the same shift that he would go out for making some purchases. Both of them did not notify the supervisor, reflecting the lax office discipline and deficiency in staff management. The supervisor only came to know the defaulter’s unauthorised absence when the latter reported to the Department about his arrest by a LEA.

Upon the Commission’s request, the Department has subsequently enhanced its monitoring of staff attendance at the venue with staff supervision tightened up. Noting that there are other offices with staff working on shifts, we have also advised the Department to –

(a) consider extending the monitoring measures to all these offices;

(b) clearly advise all staff of the standard of conduct required to ensure that proper office discipline is maintained at all times; and

(c) remind all supervisors that they are held accountable in maintaining both office operation and proper office discipline under their purview.

Case 5F

A complaint was received by a Department alleging that the officers working in an outstation office had left their workplace earlier than their scheduled off-duty time without authorisation. After investigation, the Department found that the majority of officers working in the outstation office had committed the misconduct acts of unauthorised absence over a prolonged period of time. Worse still, the defaulting officers had made false entries in their attendance records. Although disciplinary punishments were imposed on the defaulting officers given their established acts of misconduct, the supervisor was exculpated on grounds that he did not work in the same outstation office with his subordinates.

The Commission was disappointed to note the lax office discipline and poor integrity of the officers concerned, as well as the syndicated nature of the misconduct acts committed by them. The concerned office had then operated on a three-shift pattern to provide round-the-clock support services, with a relatively long overlapping period of two consecutive shifts to allow handover of duties. As defended by the defaulting officers concerned, they thought that they could leave work early after handing over their duties to the officers on the following shift, thereby resulting in the habitual unauthorised absence.

Upon discovery of the case, the Department has stepped up its monitoring on staff attendance. However, the wilful disregard of office discipline has reflected poorly on the defaulting officers and also exposed the Department’s inadequate staff supervision.

The Commission has drawn the case to the personal attention of the HoD and invited the Department to conduct a critical and comprehensive review on its staff management system, with a view to upholding the standard of office discipline and strengthening the supervisory accountability. The Department was also requested to review the shift pattern of the office to prevent the recurrence of similar misconduct acts and to ensure the gainful deployment of staff.

While this case might be an isolated one, CSB, taking into account its gravity, has also taken part in the review, advising the Department ways to step up its office discipline further and strengthen its staff supervision through the adoption of various management measures and technology solutions. The Commission fully supports their concerted efforts and looks forward to the review report to be submitted by the HoD.

The Commission was disappointed to note the lax office discipline and poor integrity of the officers concerned, as well as the syndicated nature of the misconduct acts committed by them. The concerned office had then operated on a three-shift pattern to provide round-the-clock support services, with a relatively long overlapping period of two consecutive shifts to allow handover of duties. As defended by the defaulting officers concerned, they thought that they could leave work early after handing over their duties to the officers on the following shift, thereby resulting in the habitual unauthorised absence.

Upon discovery of the case, the Department has stepped up its monitoring on staff attendance. However, the wilful disregard of office discipline has reflected poorly on the defaulting officers and also exposed the Department’s inadequate staff supervision.

The Commission has drawn the case to the personal attention of the HoD and invited the Department to conduct a critical and comprehensive review on its staff management system, with a view to upholding the standard of office discipline and strengthening the supervisory accountability. The Department was also requested to review the shift pattern of the office to prevent the recurrence of similar misconduct acts and to ensure the gainful deployment of staff.

While this case might be an isolated one, CSB, taking into account its gravity, has also taken part in the review, advising the Department ways to step up its office discipline further and strengthen its staff supervision through the adoption of various management measures and technology solutions. The Commission fully supports their concerted efforts and looks forward to the review report to be submitted by the HoD.

Omission and non-performance of duties should have been detected and avoided if supervisors discharge their supervisory and monitoring responsibilities properly and diligently.